Feeling down or depressed at points in life is a common experience, with a lifetime prevalence rate of about 8% in Canada (Canadian Mental Health Association). Despite this, many of us feel lost in terms of what we can do to address the sadness, lack of energy, low motivation, or general sense of emptiness that often accompanies this condition. This may be a function of the sometimes-insidious nature of depression, which can creep up on a person slowly and gradually. When we finally realize that things aren’t going so well, we might already be caught in a cycle of isolation, avoidance, fatigue, and just feeling crappy.

Start with theory…

When feeling stuck or discouraged, it can be helpful to turn to a theory or model for guidance. Many people have heard of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), whether explained by a counsellor, or something learned at a workshop or professional training event. CBT is an empirically validated approach to the treatment of depression and many other mental health disorders, and provides a useful framework to apply practical approaches to address low mood.

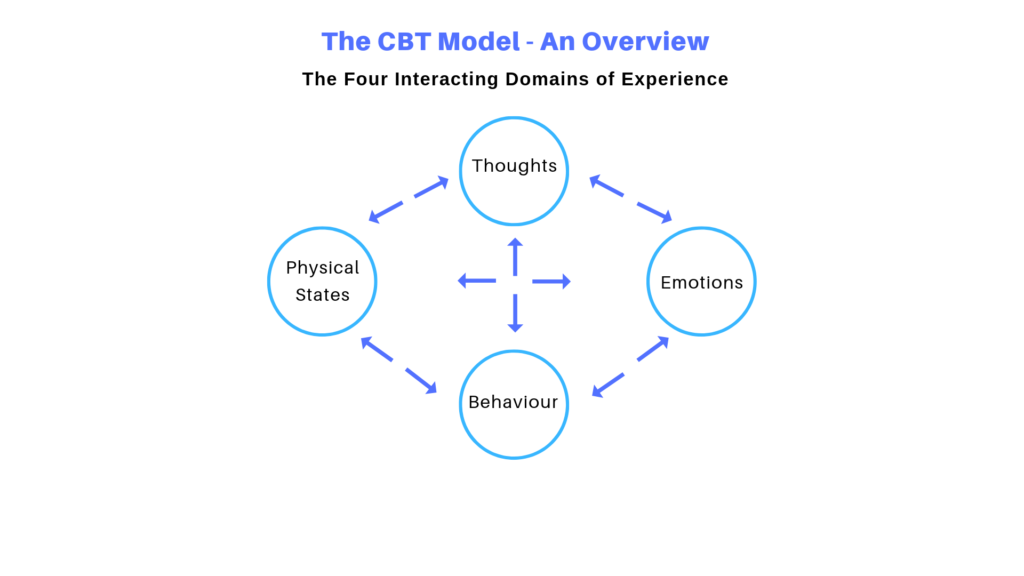

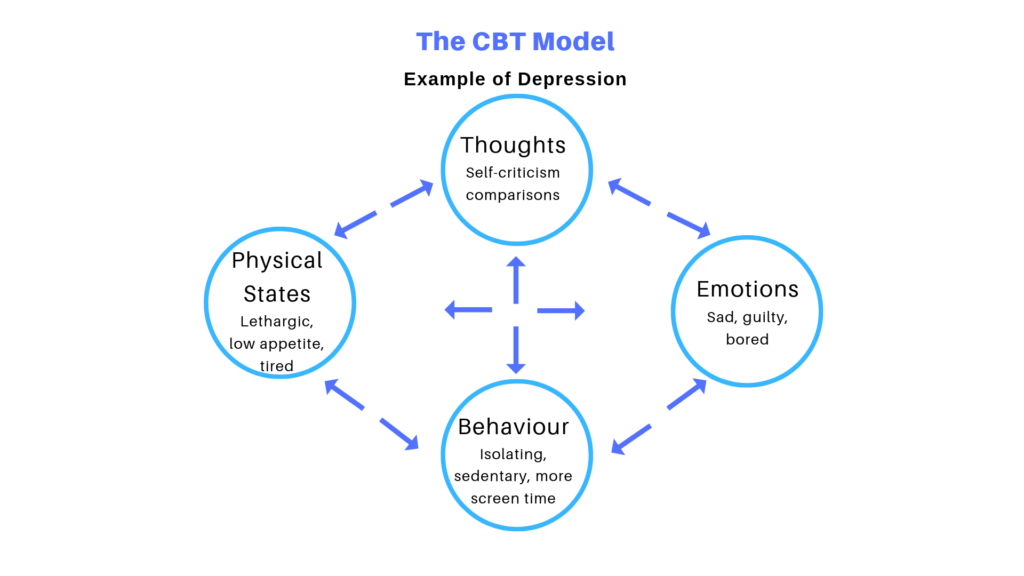

In a nutshell, CBT conceptualizes a person’s overall experience as an interaction between our thoughts, feelings, behaviour, and physical state. Because our environment also has some influence on how we think, feel, and act, this is considered a contributor to our overall experience as well.

Now, it’s fair to say that if we could simply change how we feel, therapy likely wouldn’t be a thing, as we’d all just decide to feel happy or excited. Similarly, although working to change one’s pattern of thinking might seem simple enough, in practice it can be quite difficult.

It’s true that certain techniques, such as thought-stopping, or finding evidence for or against a thought, can be useful in addressing patterns of thinking. However, these techniques are effortful, require some skill and practice, and are far from automatic. Further, if we are really struggling with powerful emotions, our thinking often becomes quite extreme, and our attention can become fixated – making efforts to intentionally adjust our thought-processes more difficult.

So what can I do?

This leads to the discussion of how intentional changes to our behaviour can influence the other experiential domains of physical states, emotions, and our thinking patterns. After all, we have to start somewhere, so it makes the most sense to start with the domain over which we have the most-control – which is of course our behaviour.

You might have heard that physicians or therapists often ‘prescribe’ exercise as a means of improving mood. To some people, this can be perceived as somewhat patronizing, as getting a bit more exercise (in their experience) is not likely to make a big difference.

And this might be true.

However, as a therapist, I think what is often missing when someone is encouraged to increase their activity level is an accompanying explanation of why this would be seen to be helpful. I don’t know about you, but I’m more-inclined to try something if someone carefully explains the theoretical reasoning behind it!

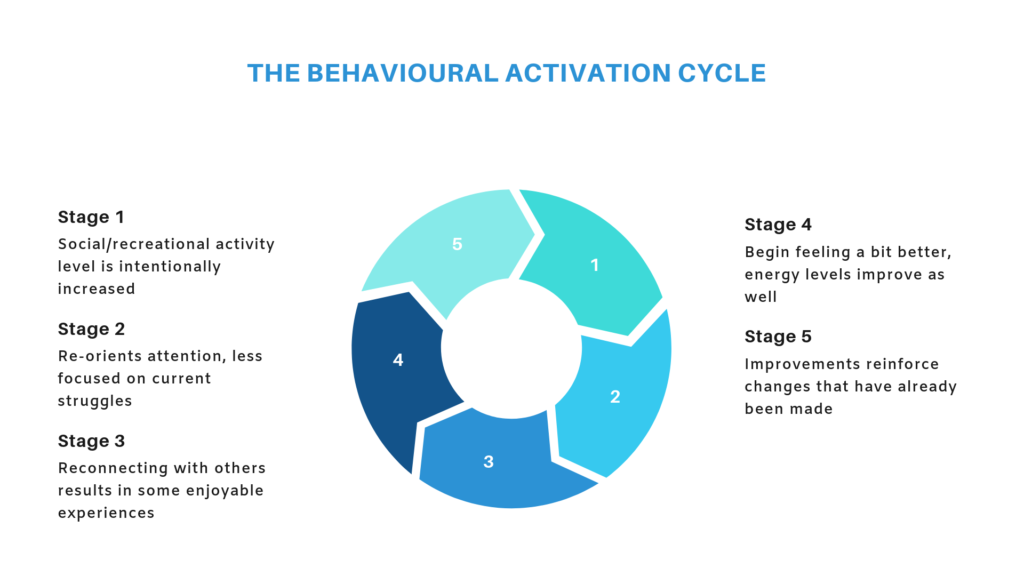

In truth, increasing our activity levels (more-broadly speaking) – whether this relates to exercise, healthy social activity, or engagement in enjoyable hobbies – is often a great place to start. Here’s why: according to the CBT model, a change in one domain of experience will have some impact on all the other domains as well, as they are all inter-connected.

One caveat that should be mentioned, however, is that this is not easy. In fact, nothing about depression is easy. The biggest mistake that many people make (therapists and individuals with depression included) is to assume that behavioural activation is a relatively straightforward concept, and therefore should be simple to apply in practice.

It is not.

However, the idea of behavioural activation is grounded in solid theory and empirically supported evidence. I would say this: applying the principle of behavioural activation is definitely not easy – but it is quite likely to help you feel better as an initial step, after which time additional strategies will need to be incorporated to make continued progress.

Let’s use an analogy: imagine you are at a stop sign on a mountain bike in the highest gear. It is SUPER hard to get going at first, and the experience is not rewarding in the least. Pretty-much just feels work.

But!

Once you get a bit of momentum, you start to notice that you are beginning to enjoy yourself a bit more, feeling the breeze in your hair, and you realize it doesn’t seem as hard to keep moving once you have a bit of momentum.

As in this scenario, when we make an effort to include more activity into our daily/weekly routine, it may not feel like anything is changing – in fact it might be downright exhausting. Remind yourself of the overall theory, and that this can be expected at first. In time, it is likely that you will start to notice small improvements or even refreshing moments along the way, which helps to reinforce the changes you have made.

If you have been really struggling with sadness, low energy, or difficult thoughts, I really encourage you to reach out to a therapist or your family doctor for additional support. Also, keep the concepts outlined above in mind as a way to make some initial progress.

Tom Nakonechny, R. Psych